New Cultures of Work:

A Syllabus

New Cultures of Work is a course at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, first offered in Spring 2022. The accompanying syllabus was crafted with young artists, designers, and writers in mind. This course, however, is not about the agency or autonomy of the creative act; instead, it focuses on the structural imperative to be a productive worker. Participants are thus invited to study, debate, and rethink their relationship to labor. In the first part of the course, we undertake a historical survey of socialist, feminist, and antiracist struggles for a less labor-intensive existence. These perspectives are presented in loosely chronological order, which also allows us to study distinct paradigms of capitalism — from the early industrial era to late-twentieth-century deindustrialization, and finally, our own crisis-ridden present. During the last weeks, we take stock of contemporary discourses on automation, precarity, and “hustle culture.”

We open with Harun Farocki’s Workers Leaving the Factory (1995): a meditation on the intertwined histories of cinema and industrial labor since the Lumière Brothers filmed their own employees fleeing at the end of a shift. Our first reading is Adam Smith’s essay on the new divisions of labor that were displacing craft production in the late-eighteenth century, launching enormous strides in productivity. As Smith himself acknowledged, however, the new plenitude that greeted consumers was mirrored by an impoverishment of their function as producers. Work became increasingly deskilled and fragmented. Next, we read Karl Marx’s “Working Day” chapter from Capital, volume one. Marx investigates the nineteenth-century factory system, where the continued degradation of work has upended the natural division between night and day — and has in some cases assigned more extreme work schedules to children than adults. Legal limitations to such exploitation, as Marx goes on to argue, would later generate new demands for productivity-enhancing technologies.

A unit on technology and factory discipline follows. We begin with Gavin Mueller’s recent reappraisal of Luddism, which links historical agitation against mechanization and deskilling to the contemporary domination of technology firms in politics and everyday life. Echoing this provocative mixture of timelines, the paired screening Bisbee ’17 documents an Arizona community’s re-enactment of a mass eviction of striking miners 100 years earlier. Next, we turn to E.P. Thompson’s account of the introduction of the time-clock into the earliest factories, along with Harry Braverman’s analysis of the “scientific” rationalization of twentieth-century labor processes. As Thompson shows, the modern work day — and even our basic sense of what constitutes an hour or a year — was a violent imposition that met fierce resistance. As the Braverman chapters illustrate, human life later became welded to market exchange as basic necessities increasingly took the form of commodities. This unit ends with three shorter readings on the lives of queer proletarians. In addition to expanding the discussion beyond the “classical” paradigm of the male breadwinner, these texts offer an alternate perspective on capitalist work: the isolation and alienation of the wage could also be experienced as a welcome form of independence from traditional expectations of family and work.

The following two weeks further complicate the story of the modern workplace by introducing postwar perspectives on unwaged housework and structural inequality in employment. We begin with Ruth Schwartz Cowan’s study of domestic labor, which demonstrates that modern appliances in middle-class homes actually increased the workload of housewives. An accompanying reading from Adrian Forty shows how these contradictions came to be embedded in the material culture of domesticity. Next is James Boggs’s pamphlet on black-led labor struggles, which reaches similar conclusions: factory automation in the 1960s had not led to decreased hours or increased pay, but rather a brutal intensification of the most dangerous, repetitive, and underpaid work — where it did not eliminate such jobs altogether. An accompanying excerpt from Eldridge Cleaver’s outline of the Black Panther Party program emphasizes the centrality of technology and the labor process to black radical thought of this period. The paired documentary Finally Got the News (1970) follows the League of Revolutionary Black Workers in their struggle within and against Detroit’s white-dominated unions.

Feminist and black radical histories also inform Kathi Weeks’s book The Problem with Work, which is the focus of a theory-oriented unit at the midpoint of the course. Weeks traces the transformation of labor into a particular kind of moral virtue in capitalism — an ideological trick that Marx was particularly fond of skewering. In a subsequent chapter, however, Weeks demonstrates that Marxism itself produced a new “socialist” work ethic, which could be just as demanding and extractive as its capitalist analogue. The accompanying screening is Bill Clinton’s 1996 announcement on what he called “the end of welfare as we know it”: a speech that emphasizes the longevity of this linkage between labor and virtue.

In the next unit, our readings turn to empirical observation and personal testimony. First, we consult two important ethnographies of working-class life. Paul Willis’s study of British teenagers destined for factory jobs in the 1970s is paired with selections from the Up! series documentaries (1964 and 1977), which closely observe the internalization of class as an identity. We then turn to Jennifer Silva’s study on coming of age in the neoliberal US, amid a fraying social safety net and dwindling job security. Finally, we read first-hand testimonials from three distinctly contemporary types of worker: a haunted but coolly analytical web developer, a barista with an encyclopedic knowledge of financialized property relations, and a warehouse worker who vividly channels the inbuilt violence of Amazon’s business model. This unit concludes with a screening of Godard’s Tout va Bien (1972), which probes the tradition of “workers’ inquiry” in fictional form.

The final unit consists of recent writing on the transformation of working conditions in the wake of new technological capabilities and, even more importantly, various economic crises since the 1970s. First, Jason Smith’s short history of automation, drawing on Marx and Boggs, argues that technological innovation can easily coexist with stagnating wages, underemployment, and a growing “servant economy.” We then read two arguments on what it would take to escape these conditions. Whereas Aaron Bastani argues for a techno-utopian future of “Fully Automated Luxury Communism,” Aaron Benanav counters that the “labor-saving” promises of automation have consistently been exaggerated. Rather than trust new inventions to liberate us from labor, he argues, we must invent new social relations that minimize, enrich, and more equitably distribute it — a project, it turns out, that will take a great deal of work.

The last session, finally, turns toward its participants: a group of students preparing for uncertain futures in the culture industries and a professor working at the lowest rung of the adjunct hierarchy. Readings by Silvio Lorusso, Angela McRobbie, and the Precarious Workers’ Brigade interrogate the independent artist, the perpetual student, and the scrappy entrepreneur as role models for a society whose constituents have been left to fend for themselves. Our last screening, Andrew Norman Wilson’s Workers Leaving the Googleplex, returns to Farocki’s fascination with continuity and change in work and its representation; recalling key scenes from Tout va Bien, it also stages an uneasy encounter between high-tech “creatives” and deskilled factory hands.

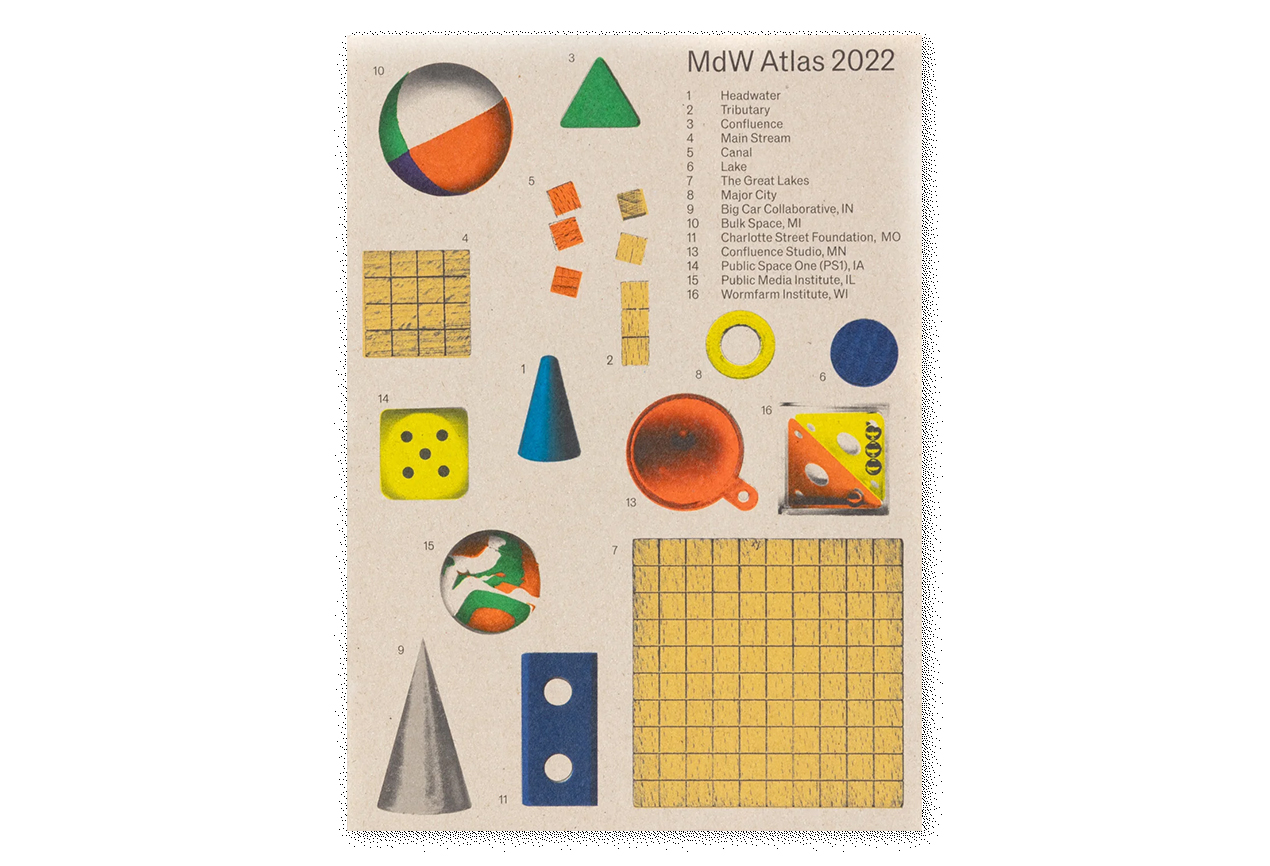

“New Cultures of Work: A Syllabus” (2022) was commissioned for MDW Fair’s “Atlas” project and edited by Kristi McGuire. Mairead Case was series editor.