Interview, 2024

CLD Why place design in the history of capitalism?

JDB As our textbooks tell us, graphic and industrial design emerged out of the modern separation of planning and production. From the Arts and Crafts movement to the Bauhaus, design theory and criticism were centrally concerned with mass production and the decline of craft. There were many varieties of modernism, but each tried to understand and respond to these new conditions of work and life. Later, particularly in the postwar US, the design professions helped to adapt modernism to the institutions of advanced capitalism.

This is a familiar story, which design historians have often explained in terms of “industry,” “rationalism,” or “abstraction.” All of those concepts fit, but I think that capitalism — which implies order, but also contradiction and crisis — has more explanatory power. Capitalist society has very particular dynamics; it generates particular needs. Starting from that context can offer a more critical perspective on both the canon and present-day practice.

CLD What can the history of typography teach us about changes in the world of work?

JDB Designers are often curious about the politics of design. This usually means asking how design acts on society. I try to reverse this question: to ask, instead, how society has shaped design. One way to do that is to examine how the labor of design has changed over time.

In the late nineteenth century, the craft of typography was partially mechanized. Later, typography abandoned its traditional materials, merging with new media like film and cathode-ray tubes. More recently, it was encoded into software. All of these transformations changed the way designers work. But they also affected many other types of workers. In this way, graphic design can be connected to the rise and fall of powerful printers’ unions in North America, and thus to a complex story about labor, gender, and race. Rethinking design history as labor history might also help us to anticipate future changes in our working conditions.

CLD Why is autonomy an important theme in design?

JDB Most designers I know want more autonomy. But that can mean different things. The Soviet avant-garde, for example, criticized the autonomy of the fine arts; they wanted to insert themselves directly into production and politics. They did this, however, to build a society that could develop autonomously of capitalist constraints. Once modernism comes to be associated with capitalism, this changes: avant-garde designers now assert their autonomy by experimenting with ideas and forms that seem incompatible with commercial interests.

The problem is that capitalism is very good at assimilating critique. The contemporary design discourse can be frustrating because many designers use oppositional, critical language, but often in very ambiguous ways. In this context, “autonomy” might mean resisting market pressures, but it might also mean reinforcing the status of the profession, or even advancing an individual designer’s career. A debate on its meaning would be clarifying: Autonomy for whom? Autonomy from what?

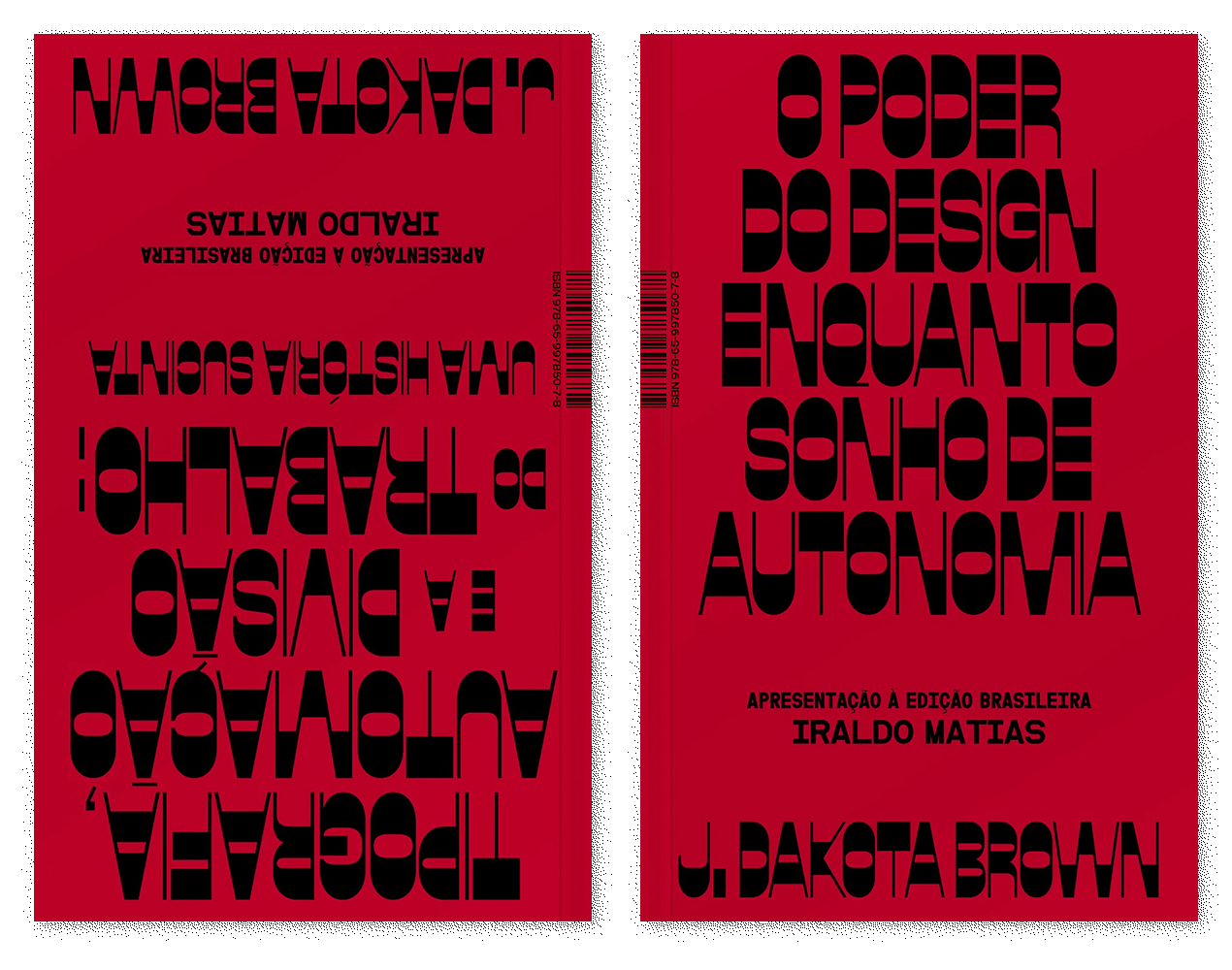

This exchange was published in Portuguese for the release of Automação e Autonomia: Dois Ensaios sobre Design (2024). The book was edited and designed by Tereza Bettinardi and translated by Eduardo Souza and Gabriela Araújo, with a new introduction by Iraldo Matias.